Translate this page into:

Disseminated langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as decompensated childhood cirrhosis

*Corresponding author: Khushboo Tekriwal, Department of Radiology, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. khushbootekriwal300995@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Tekriwal K, Bhoir AA, Badhe PV, Alam Z. Disseminated langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as decompensated childhood cirrhosis. Case Rep Clin Radiol. 2024;2:26-30. doi: 10.25259/CRCR_46_2023

Abstract

Childhood cirrhosis is a rare disease of multifactorial etiopathogenesis. One of the rare underlying causes is Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). The multifocal multisystemic variant of LCH can rarely involve the hepatobiliary system. Indirect and direct forms of hepatobiliary involvement are known. Early diagnosis of underlying liver involvement in cases of LCH is crucial to prevent decompensation and ameliorate prognosis post-liver transplantation. This is a case of an 18-month-old male child who developed cutaneous lesions in the early infancy. He was brought to clinical attention due to progressively increasing abdominal girth. His laboratory, clinical and radiological examination suggested multisystem pathology, subsequently confirmed on biopsy as LCH with predominant involvement of hepatobiliary, pulmonary, and integumentary systems. Unfortunately, he succumbed within a week of diagnosis.

Keywords

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Hepatic involvement

Jaundice

Cirrhosis

INTRODUCTION

Childhood cirrhosis is a rare disease of multifactorial etiopathogenesis. One of the rare underlying causes is Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). The multifocal multisystemic variant of LCH can involve the hepatobiliary system. Early diagnosis of underlying liver involvement in cases of LCH is crucial to prevent decompensation and for statisfactory prognosis post-liver transplantation.

CASE REPORT

An 18-month-old male child was brought to medical attention when his mother noticed gradually progressive abdominal distension, swelling in both feet, yellowish discoloration of eyes, and clay-colored stools for 3 months. A history of intermittent low-to-moderate grade fever episodes was present for the past 8 months associated with skin rashes. On clinical examination: There was hepatosplenomegaly with signs of gross ascites. Icterus and pallor were present. There were cutaneous lesions such as seborrheic dermatitis over the scalp, scaly lesions over palms with a pinpoint petechial rash over the soles, dorsum and palmer aspects of hands, skin-colored maculopapular rash over the forehead, and dorsum of both hands [Figure 1].

- Cutaneous lesions in an 18-month-old male child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis who presented with abdominal distension and signs of jaundice. (a and b) Skin-colored maculopapular rash over the forehead and dorsum of the hand. (c) Pinpoint petechial rash over the sole. (d) Scaly lesions over the palm. (e) Seborrheic dermatitis over the scalp.

His hemogram showed a 5.6 g/dL haemoglobin level, increased reticulocytes >3.2%, with a leucocyte count of >29,000. Liver function tests were also significantly deranged with total serum bilirubin of >7 mg/dL (direct bilirubin levels of 4.6 mg/dL), mildly raised liver enzymes (serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase - 172 U/L and serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase - 94 U/L), hypoalbuminemia (3.6 g/dL), and markedly increased prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (135 s/12.4). There was an approximately 10-fold rise in inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Workup for hepatitis B and C markers was negative. Serum ferritin, ceruloplasmin, and copper were within normal limits.

A sonographic evaluation of the abdomen was advised, which confirmed the presence of hepatosplenomegaly and gross ascites. There were a few enlarged lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum and periportal region. A persistently collapsed gallbladder was seen; however, the size, morphology, and mucosal enhancement were normal. There was increased periportal cuffing. The intra- and extrahepatic biliary systems were not dilated. Based on the laboratory parameters and sonographic evaluation, the causes of childhood cirrhosis were considered with a pediatric end-stage liver disease score of >60. The presence of cutaneous lesions was unusual for common causes of childhood cirrhosis. A dermatology opinion was requested, and the possibility of a multisystemic variant of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) was raised.

A frontal chest radiograph was performed, which showed reticulonodular opacities in both lung fields suggesting an underlying infective process [Figure 2]. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed variable-sized cysts [Figure 3a] and nodules in anterior segments of both upper lobes with patchy areas of fibrosis [Figure 3b]. There was relative sparing of both cardio-phrenic angles [Figure 3c]. Contrast-enhanced abdomen CT confirmed the presence of collapsed gallbladder [Figure 3d]. In addition, it showed hypodensities along the intrahepatic portal and biliary tracts [Figure 3e] and tiny discrete hypodense non-enhancing nodules scattered in the liver parenchyma [Figure 3f]. There is hepatosplenomegaly with gross ascites [Figure 3g], small enhancing nodules were also seen in the extraperitoneal space, with few enlarged lymph nodes in the periportal and retroperitoneal regions.

- An 18-month-old male child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis presented with cutaneous lesions, abdominal distension, and signs of jaundice. Frontal chest radiograph shows reticulonodular opacities in both lung fields.

- An 18-month-old male child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis presented with cutaneous lesions, abdominal distension, and signs of jaundice. Axial high-resolution computed tomography chest images show (a) variable-sized cysts in anterior segments of both upper lobes (black arrows) and nodules (white arrowhead). (b) Fibrotic patch (red arrow). (c) Relative sparing of both anterior costophrenic angles (region within yellow circles). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography abdomen with pelvis shows (d) collapsed gallbladder with normal enhancing mucosa (yellow arrow). (e) Hypoattenuating infiltrates along intrahepatic portal and biliary tracts (black arrowheads). (f) Tiny hypodense non-enhancing liver lesions scattered throughout the liver parenchyma (within white circles). (g) Hepatomegaly with gross ascites tracking into the left scrotal sac.

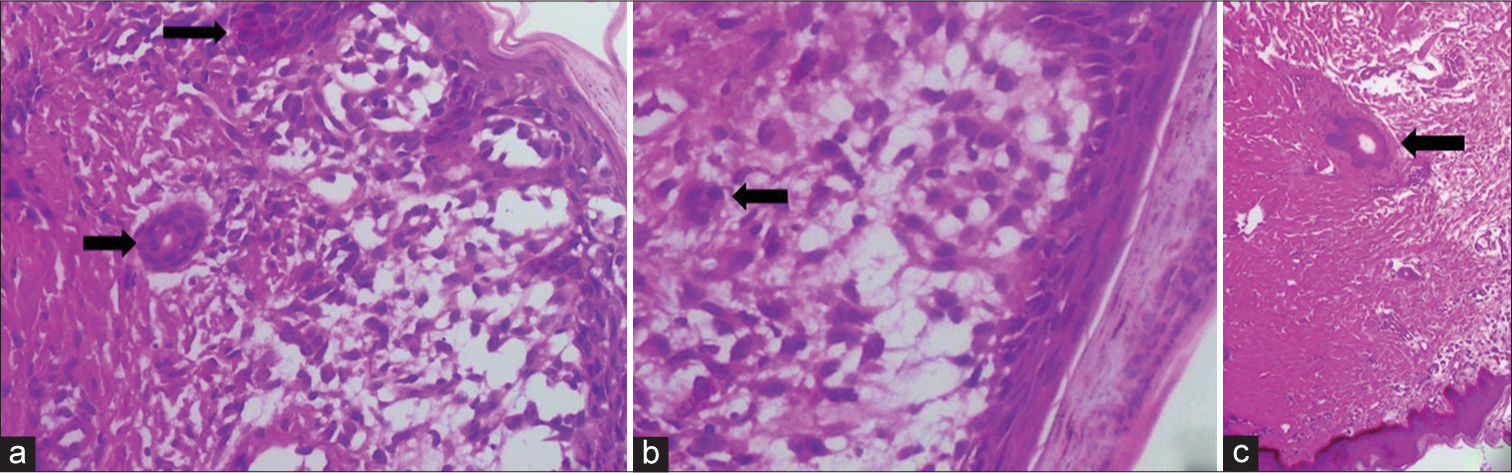

One of the cutaneous lesions was biopsied, revealing nondendritic multinucleated giant cells in the dermis [Figure 4]. On immunohistochemistry, these cells stained positive for S100 and CD1a, confirming the diagnosis of Letterer–Siwe disease. Unfortunately, the child succumbed within a week of diagnosis. Histopathological examination of postmortem specimens of the liver showed periportal infiltration of eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells.

- An 18-month-old male child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis presented with cutaneous lesions, abdominal distension, and signs of jaundice. A punch biopsy from one of the cutaneous lesions shows (a and b) multinucleated giant cells in the dermis (arrows). These cells stained positive for CD1a and S100 (image not included). (c) An antigen-presenting multinucleated dendritic cell in the dermis (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Childhood cirrhosis is a rare disease. It has a multifactorial etiopathogenesis such as cholestasis, infective (viral), hereditary, autoimmune, metabolic, or an underlying cardiac disease. Very rarely, involvement of the hepatobiliary system by a multisystemic variant of LCH has been reported.[1-3]

Langerhans cells are multinucleated giant cells which express CD1a, S-100, and Langerin proteins. Excessive proliferation of these cells results in diseases under the LCH spectrum. Approximately 2–10 cases per 1 million children suffer from LCH.[4,5] with equal gender predilection.[6] However, in isolated cutaneous involvement, male predilection is seen. LCH can be broadly divided into unifocal, multifocal unisystem, multifocal multisystem, or isolated pulmonary variant. Unifocal LCH can involve one or multiple bones. Multifocal unisystem variant involves bones and skin and can be associated with fever and diabetes insipidus secondary to the pituitary stalk. Multifocal multisystem variant or the Letterer–Siwe disease can affect bones, endocrine, ocular, central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, spleen, skin, lung, and hepatobiliary; the last three organ systems were involved in our case. More than two-thirds of the cases of Letterer–Siwe disease involve a single organ system with bones and skin as the most common sites.[5,7]

The radiological and clinical features widely vary based on the affected sites [Table 1]. There are two known patterns of hepatobiliary involvement in LCH: (a) Indirect involvement: Activated macrophages result in hepatosplenomegaly and hypoalbuminemia and (b) direct involvement.[8] Direct involvement is further of two types, (a) without infiltration of Langerhans cells along portal tracts and (b) with the predominance of Langerhans cells along portal tracts. Contrast-enhanced CT reveals low attenuation lesions in the liver with or without distorted intrahepatic biliary system with sclerosing cholangitis-like appearance.[8]

| S.no | Organ involved | Radiological features | Clinical presentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bones | Skull: Punched out lesions with or without soft tissue. Bevelled edges on tangential view. Vertebra: Vertebra plana Mandible: Floating teeth sign |

Skull: Focal calvaria swelling /pressure symptoms secondary to foraminal stenosis Orbital wall: Proptosis Temporal bone: Mastoiditis or Deafness Spine: pain Mandible: gingival bleeding |

| 2. | Lymph nodes | It can result in massive lymphadenopathy. Most common site: Cervical |

Pressure effects- over airways or biliary system Dyspnoea or obstructive jaundice |

| 3. | Thymus | Punctate calcification in the enlarged thymus. | Anterior mediastinal mass. Differential-Teratoma(has larger calcifications). |

| 4. | Pulmonary | Upper lobe predominant reticulonodular opacities, cysts or honeycombing in progressed disease. Sparing of costophrenic angles |

Cough, dyspnoea and chest pain |

| 5. | Liver | Hepatosplenomegaly Low attenuation lesions in the liver with or without distorted intrahepatic biliary system with sclerosing cholangitis-type appearance. |

Icterus Clay-coloured stools. Bleeding diathesis Hepatosplenomegaly Ascites Pallor |

| 6. | GIT | Nonspecific can present as multifocal strictures | Nonspecific |

| 7. | Endocrine | Thickened pituitary stalk (>2.5mm) with intense post-contrast enhancement and loss of posterior pituitary bright spot on T1 weighted MRI | Diabetes Insipidus |

| 8. | Skin | - | Scaly erythematous red or brown papules |

GIT: Gastrointestinal tract

Chemotherapy has shown some promising results in the treatment of LCH. Hepatic involvement, if not recognized in the early disease course, can progress to decompensated cirrhosis, significantly affecting the prognosis.

CONCLUSION

LCH can present as a multisystem disease with variable prognosis based on the organ and extent of involvement. Liver involvement in the LCH is an important prognostic marker. Hence, early recognition is of utmost importance in deciding the success of liver transplantation in these patients.

TEACHING POINTS

Hepatobiliary involvement in LCH is rare and seldom discussed. Overlooking the possible involvement can invariably be fatal. Early diagnosis of underlying liver involvement in cases of LCH is crucial to prevent liver failure and ameliorate prognosis post-liver transplantation. Hence, in every suspected or confirmed case of disseminated LCH, an underlying hepatic involvement should be explicitly looked for.

MCQs

-

Langerhans cell histiocytosis least commonly affects which organ system?

Skeletal

Pulmonary

Central nervous system

Cutaneous

Answer Key: c

-

Endocrine system involvement in Langerhans cell histiocytosis can result in?

Diabetes mellitus

Cushing’s disease

Diabetes insipidus

Conn’s syndrome

Answer Key: c

-

All of the following are related to Langerhans cell histiocytosis except?

Rosai-Dorfman disease

Eosinophilic granuloma

Letterer–Siwe disease

Hand Schuller Christian triad

Answer Key: a

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Liver involvement in Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: A study of nine cases. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:370-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disseminated langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as cholestatic jaundice. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:SD03-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis and sclerosing cholangitis in adults. Rev Mal Respir. 2004;21:997-1000.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of langerhans cell histiocytosis in children in Denmark, 1975-89. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1993;21:387-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and clinical features of langerhans cell histiocytosis in the Uk and Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:376-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The French Langerhans' Cell Histiocytosis Study Group. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75:17-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liver involvement in childhood histiocytic syndromes. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2001;17:474-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]