Translate this page into:

Primary pulmonary osteosarcoma: A rare malignancy of the lung with histopathologic correlation

*Corresponding author: Anitha Mandava, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Basavatarakam Indo American Cancer Hospital and Research Institute, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. kanisri@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Mandava A, Yalamanchili R, Kodandapani S, Koppula V. Primary pulmonary osteosarcoma: A rare malignancy of the lung with histopathologic correlation. Case Rep Clin Radiol. doi: 10.25259/CRCR_176_2023.

Abstract

Primary pulmonary osteosarcoma (PPO) is an uncommon aggressive mesenchymal neoplasm of the lung characterized by the production of osteoid matrix. Calcified metastases from osteosarcoma of bone are more common in the lung rather than PPOs, and the differentiation between these two entities is important for the management. The diagnosis of PPO requires exclusion of primary osteosarcoma elsewhere in the body and also histopathological confirmation. We report a case of primary osteosarcoma of the lung with a brief review of literature.

Keywords

Primary pulmonary osteosarcoma

Computed tomography

F-18 FDG PET-CT

INTRODUCTION

Primary pulmonary osteosarcoma (PPO) is a rare osteoid producing mesenchymal neoplasm of the lung. We report the imaging features in a case of PPO with histopathological correlation.

CASE REPORT

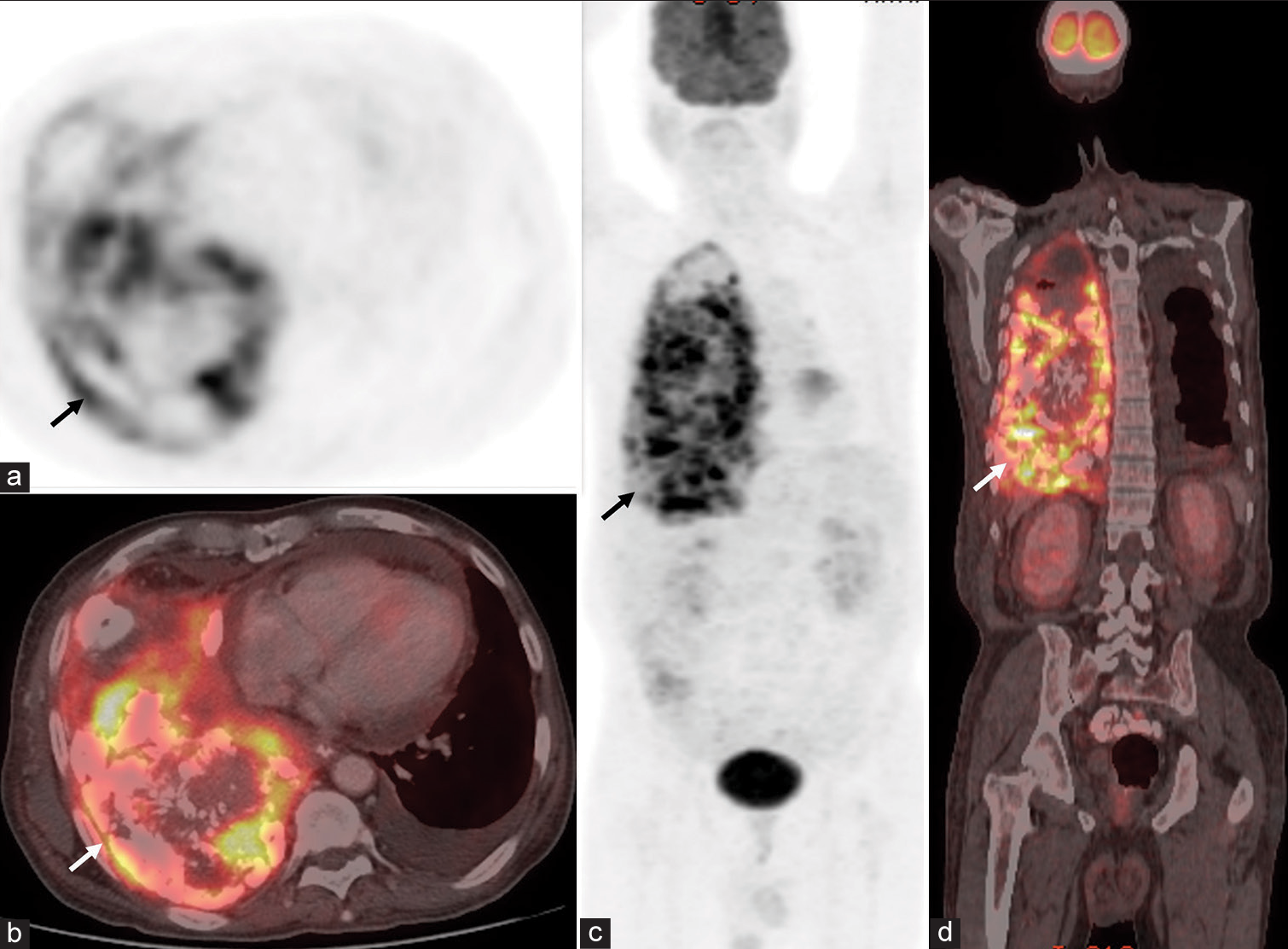

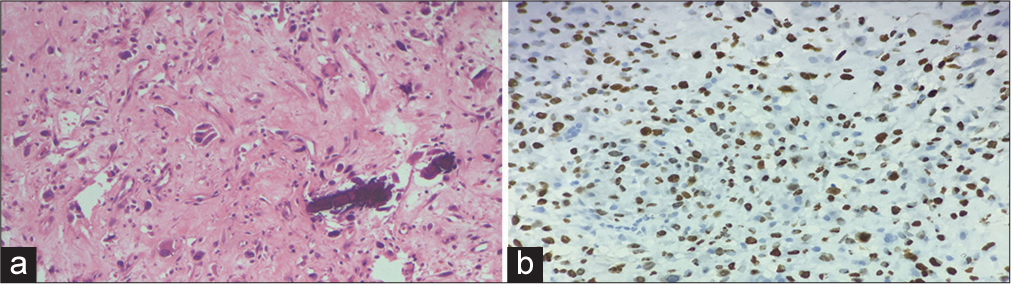

A 64-year-old man presenting with chest pain and breathlessness was referred for a chest radiograph and whole body 18 F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT). Chest radiograph revealed diffuse haziness with inhomogeneous lobulated dense opacities in the right hemithorax. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the chest revealed a large heterogeneously enhancing soft-tissue mass with dense irregular internal ossifications (HU >1000) in the right lung. Bilateral pleural effusions, mild pericardial effusion, along with passive collapse of the right lung, are shown in Figure 1. 18 F-FDG PET/CT revealed a large hypermetabolic mass in the right lung [Figure 2]. Since no other primary lesion was seen on PET/CT, a probable diagnosis of primary pulmonary osteosarcoma (PPO) was given. CT-guided biopsy of the mass was performed; histopathology and immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of osteosarcoma [Figure 3]. The patient developed massive pericardial effusion and expired within a month.

- (a) Chest radiograph shows diffuse haziness of the right hemithorax with variably dense lobulated opacity silhouetting the right cardiac border and right hemidiaphragm. (b and c) Axial contrast-enhanced soft tissue and bone window computed tomography images show large heterogeneously enhancing soft-tissue mass with dense ossifications encasing the right hilar structures, infiltrating the pleura, pericardium, and mediastinum with mild left pleural and pericardial effusions.

- (a-b) Axial chest positron emission tomography (PET) and fusion positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) images show hypermetabolic mass with calcifications/ ossifications in right lung (arrows). Left pleural effusion is also seen. (c-d) Whole body PET and fusion PET/CT images show the right lung lesion (arrows). No other malignant lesion is seen.

- (a) Hematoxylin and eosin Stain (H&E ×40): The tumor cells show densely eosinophilic cytoplasm resembling osteoblasts along with thin, lace-like osteoid suggestive of osteosarcoma. (b) Immunohistochemistry: Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2 ×100) stain shows nuclear positivity confirming the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

PPO is a highly unusual malignant extraskeletal osteosarcoma (ESOS) arising in the lung. ESOSs are rare soft-tissue neoplasms characterized by the production of osteoid or chondroid matrix without any attachment to bones.[1] ESOS most frequently occurs in the soft tissues of lower and upper limbs, followed by the retroperitoneum.[1] However, unusual locations of ESOS include lung, breast, brain, esophagus, gallbladder, liver, kidney, larynx, parotid gland, small bowel, mesentery, and uterus.[1] Although lung is the most common site of metastases for osteosarcomas of bone, primary osteosarcoma of lung is extremely rare, with an incidence of only 0.01%.[2] The first case of PPO was described by Greenspan in 1933, and since then, <30 cases are documented in the literature.[2,3] We report a case of PPO diagnosed on CT, confirmed by PET/CT and histopathology, with a brief review of the literature.

PPO is usually seen in patients above 60 years of age with a slight male preponderance.[2,4] Patients are initially asymptomatic, and as the tumor grows large, they present late with non-specific symptoms due to the mass effect, compression, and invasion of the adjacent structures by the tumor. The most common presenting symptoms are cough, chest pain, dyspnea, fever, chills, and paresthesias of upper limbs, and in a rare instance, pneumothorax was reported at presentation.[2,3,5,6]

PPO can originate from any tissue in the lung including cartilaginous bronchial rings, reticuloendothelial tissue, fibrous stroma, mesenchymal tissue, old ossified focus of infection, and, rarely, the pulmonary artery.[6,7] Prior exposure to local radiation, asbestos and aluminum dust, chemotherapy, pulmonary tuberculosis, and trauma have all been implicated in the pathogenesis of PPO, while focal pulmonary inflammation leading to tumorigenesis has been postulated to be the mechanism.[3]

The histologic diagnosis of PPO is characterized by the presence of osteoid matrix or immature bone formed by the proliferating anaplastic spindle cells. Three diagnostic criteria have been described for a lung malignancy to be considered as PPO.[2,4]

The presence of a uniform pattern of sarcomatous tissue in the tumor without any mixed mesenchymal tissue

Production of bone or osteoid matrix by the tumor

Exclusion of primary bone tumors elsewhere in the body.

Radiologically, PPO is most often seen as a large soft-tissue mass with areas of mineralization. Chest CT scan showing large tumors in the lung with a median size of 8 cm or more with calcification or ossification and malignant features such as mediastinal invasion, lymphadenopathy, pleural invasion/ thickening/effusion strongly hints at the possibility of osteosarcoma.[3] These calcified lesions show intense uptake of the radiotracer Technetium 99m-methyl diphosphonate, and hence, bone scintigraphy is helpful in these cases to rule out primary skeletal osteosarcomas.[5,8,9] Gu et al. reported similar avid uptake of F-18 FDG in a case of PPO; therefore, whole-body F-18 FDG PET/CT is useful in characterizing the primary lung lesion and, at the same time, excluding skeletal or ESOS.[10]

PPO has an extremely poor prognosis as it is generally detected late and most patients die within a year of diagnosis.[9] PPO is not amenable to chemotherapy and radiation; therefore, complete surgical resection is the only option for management.

There are no specific radiological features to identify PPO; hence, it is important to confirm the diagnosis by CT-guided needle biopsy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Radiological differential diagnosis of calcified lung lesions includes benign lesions such as calcified granulomas and hamartomas or malignant lesions such as primary lung cancers, pulmonary sarcomas, pulmonary carcinoid tumors, and lung metastases from osteogenic or chondrogenic sarcomas [Table 1].[2,5,7,9]

| Lung lesion with calcifications | Clinical features | Imaging features and management |

|---|---|---|

| Primary pulmonary osteosarcoma | Usually seen in older adults, above 60 years of age with a slight male preponderance | Primary lesion is in lung. Surgery is the only curative option. Poor response to therapy. |

| Lung metastases from osteosarcoma of bone | Usually seen in children and young adults | Primary lesion is in skeleton, usually long bones. |

| Carcinoma lung with calcification | Usually seen in adults, above 40 years of age | Primary lesion is in lung. Amenable to multimodality treatment. |

| Granulomatous lesions with calcification | Adults | Benign lesions with good prognosis. |

CONCLUSION

The definitive diagnosis of PPO is made by correlating both histopathological and radiological findings, and in lung lesions with osteoid or bone matrix, primary skeletal or extraskeletal malignancy metastasizing to the lung should be excluded.

TEACHING POINTS

The size of the malignant mass is the single most important prognostic factor in the management of PPO and tumors measuring more than 5 cm have adverse prognosis.

Malignant lung mass with osteoid matrix on CT scan of the chest is suggestive of PPO and histopathological confirmation, bone scintigraphy, and/or whole-body PET/CT are required for definitive diagnosis.

MCQs

-

Thoracic extraskeletal osteosarcomas can occur only in

Lung

Mediastinum

Pleura and chest wall

All of the above

Answer Key: d

-

18FDG PET/CT scan in PPO shows

Increased uptake in the lesion

No uptake in the lesion

Increased uptake in the lesion, not specific for the diagnosis, needs histopathological correlation

None of the above

Answer Key: c

-

In regard to the management of PPO the following statement is correct?

PPO responds to chemotherapy

Small lesions are amenable to radiation therapy

Median age of death after diagnosis is less than a year

Recurrences are not seen after surgery

Answer Key: c

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Primary mesenteric extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Niger J Basic Clin Sci. 2013;10:95-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Primary extraosseous osteosarcoma of the lung. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:114-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primary thoracic extraskeletal osteosarcoma: A case report and literature review. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:E1088-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteogenic sarcoma of the somatic soft tissues: Clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of literature. Cancer. 1971;27:1121-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A case of pneumothorax due to primary pulmonary osteosarcoma-when a common disease coincides with an unexpected cause. Jpn J Lung Cancer. 2015;55:108-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Primary osteosarcoma of the lung: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:150-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radionuclide detection of primary pulmonary osteogenic sarcoma: A case report and review of the literature. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1110-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two cases of primary pulmonary osteosarcoma. Intern Med. 2005;44:632-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primary pulmonary osteosarcoma: PET/ CT and SPECT/CT findings. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:e209-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]