Translate this page into:

Paradox of aggressive benignity in abdominal wall

*Corresponding author: N. Suriyaprakash, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Government Medical College, Tiruppur, Tamil Nadu, India. cbesuriya@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Suriyaprakash N, Satiish RS, Kavitha D, UmaMaheshwari V. Paradox of aggressive benignity in abdominal wall. Case Rep Clin Radiol. doi: 10.25259/CRCR_93_2024

Abstract

Actinomycosis is a rare chronic bacterial suppurative infection caused by Gram-positive anaerobic bacilli belonging to Actinomyces spp. Actinomyces israelii is the most common organism causing human infections. Normally actinomycetes are seen as commensals in the oropharynx, gastrointestinal, and female urogenital system, and hence, cervicofacial, bowel, and pelvic actinomycosis are commonly encountered. Primary abdominal wall actinomycosis is a very rare presentation.

Keywords

Abdominal wall actinomycosis

Actinomycetes

T2 hypointense abdominal mass

INTRODUCTION

Actinomycetes are not ordinarily pathogenic in immunocompetent individuals; however, mucosal disruption by surgery, perforation, foreign body, or trauma may be a predisposing condition.[1] The clinical and radiological presentation of actinomycosis is variable depending on the site of involvement and duration of the disease. The common presentation includes abscess formation with discharging sinuses and fibrosis. The ability of actinomycetes to infiltrate across the fascial and connective tissue planes and form dense fibrosing masses poses significant difficulty in differentiating from neoplastic lesions and common granulomatous conditions like tuberculosis. The earlier and prompt diagnosis of abdominal wall actinomycosis is important to initiate the appropriate antibiotic therapy.

CASE REPORT

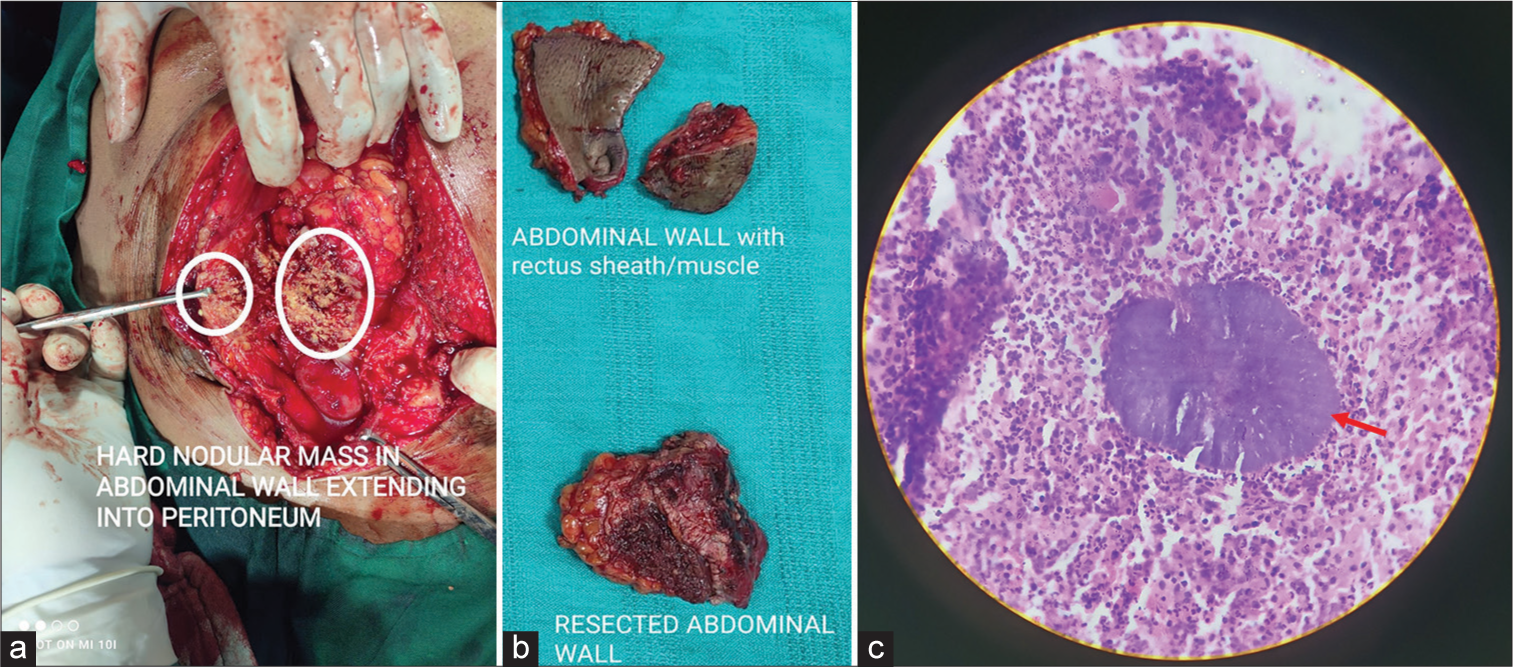

A 47-year-old male presented with complaints of pain and swelling in the midline anterior abdominal wall just above the umbilicus for a month duration. No bowel or urinary complaints. There was no history of fever or abdominal surgery/trauma. The medical and other surgical history was unremarkable. No history of diabetes/other immunocompromised status including human immunodeficiency virus infection. Ultrasound abdomen revealed an ill-defined and irregular hypoechoic lesion at the site of clinical pain and swelling with inflammation in the subcutaneous fat plane [Figure 1]. Minimal internal vascularity was noted within the lesion. No demonstrable calcification/cystic change was seen. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed an irregular minimally enhancing abdominal wall supraumbilical mass lesion with an intra-abdominal component abutting the jejunal loops with mild thickening [Figure 2]. However, there was no evidence of bowel obstruction. There was no evidence of free fluid or intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy on cross sectional imaging. Screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) depicted an irregular T1/T2 hypointense lesion with faint diffusion restriction in the midline supra-abdominal region involving the abdominal wall muscles [Figure 3]. Possibilities of abdominal wall tuberculosis, desmoid tumor, and metastases were considered. Image-guided biopsy was done and sent for histopathological examination (HPE) before treatment. After discussion by the multidisciplinary team consisting of general surgeon, microbiologist, pathologist, and radiologist, it was decided to proceed with surgical debulking [Figure 4a and 4b] and specimen for sent for pathological analysis. The typical histopathological finding includes a conglomeration of the bacilli with surrounding radiating eosinophilic lymphohistiocytic infiltration called as Splendore-Hoepelli reaction [Figure 4c]. The patient is on oral antibiotic treatment and is advised to follow-up after 6 weeks.

- (a) Transverse scan using a convex probe shows an irregular hypoechoic mass lesion with intra and extra-abdominal components (red circle). Thickening of the abdominal wall (yellow line) at the lesion site. (b) Transverse scan using a linear high-frequency probe showing extensive abdominal wall edema with hypoechoic soft tissue component (red circle). m: Mindray machine.

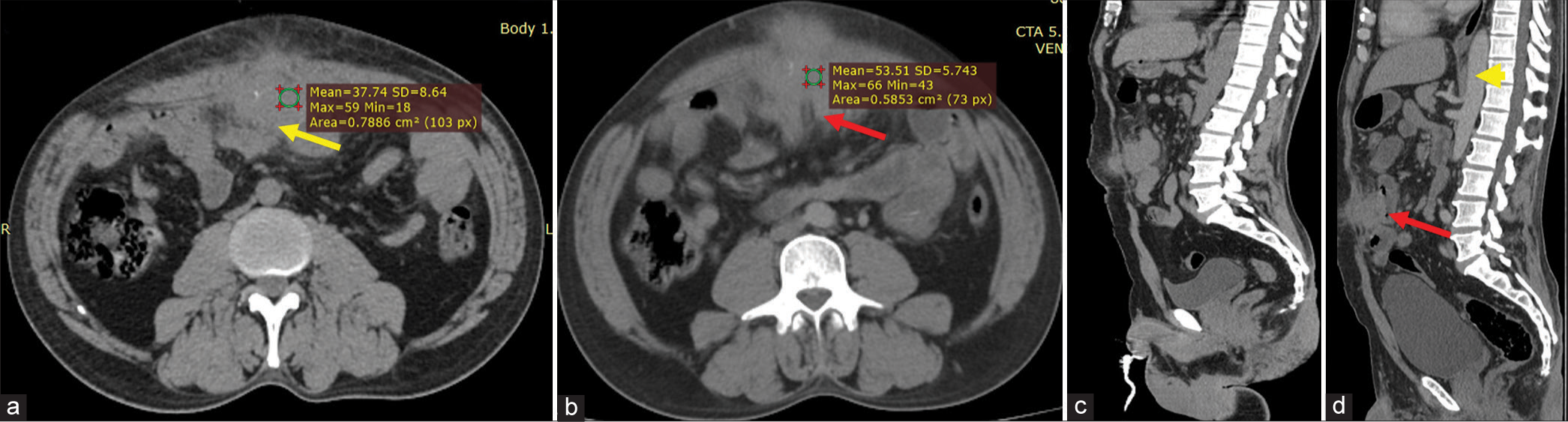

- (a) Non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) shows a irregular hypodense soft tissue lesion (yellow arrow) in the midline anterior abdominal wall just above the umbilicus. (b and c) There is minimal enhancement (red arrow) in post contrast imaging in axial and sagittal planes. No regional lymphadenopathy / free fluid in the abdominal cavity. (d) The lesion abuts the jejunal loop with mild thickening (red arrow), however, no obstruction changes were noted. Note the aorta which appears mildly hyperdense due to contrast opacification (yellow arrow head).

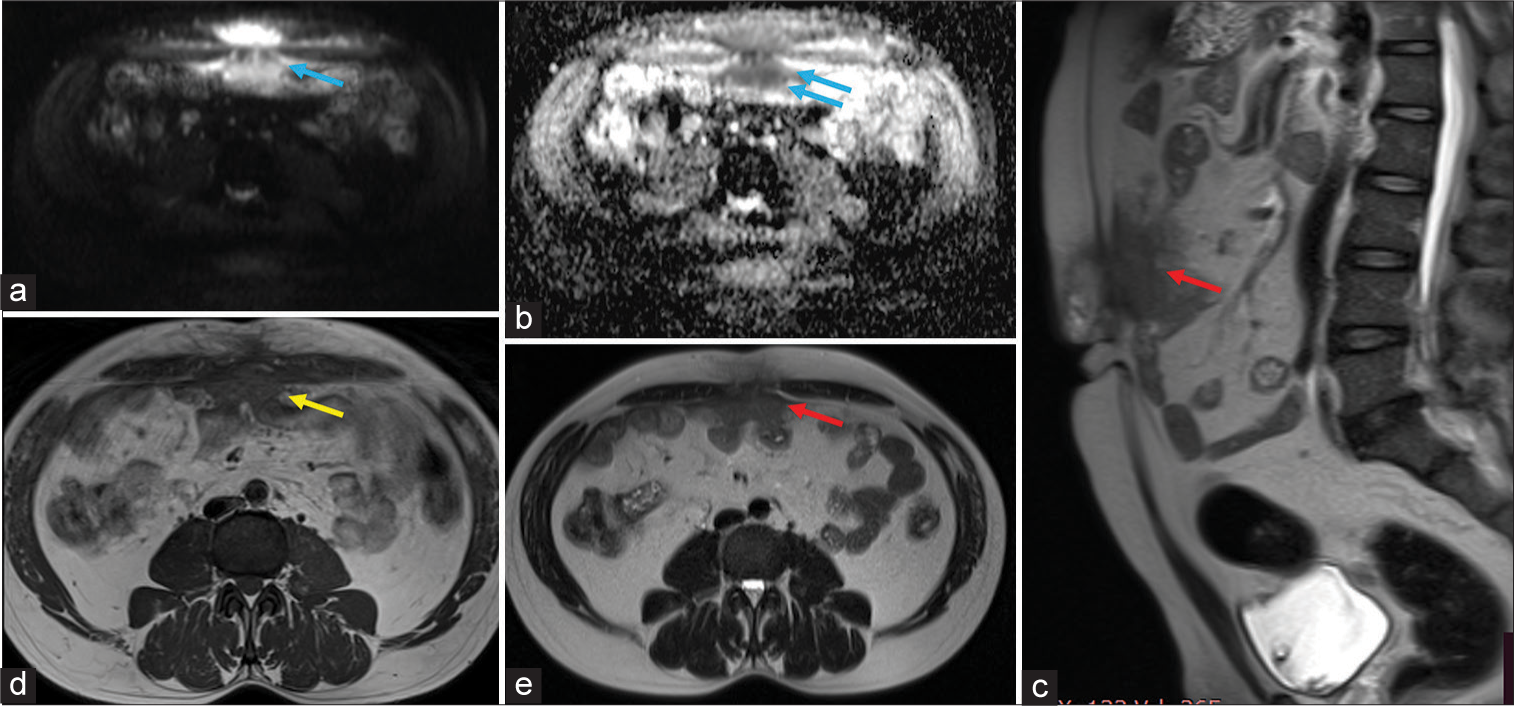

- (a and b) Axial DWI and Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) show an irregular diffusion-restricting lesion in the mid-line supra-umbilical region (blue arrows). (c) Sagittal T2WI shows a hypointense lesion (red arrow) in the anterior abdominal wall. (d) Axial T1WI reveals a hypointense lesion (yellow arrow) with minimal inflammation in the subcutaneous plane and abutting the intraabdominal bowel loops. (e) Axial T2WI shows mild thickening of the peritoneum in contact with the lesion (red arrow).

- (a and b) Intra operative specimen showing nodular mass (white circles) and surgical specimens. (c) Histopathological examination image showing the actinomycetes colonies with sulphur granules (red arrow).

DISCUSSION

Primary abdominal wall actinomycosis is a rare chronic infection caused by Actinomyces species, primarily Actinomyces israelii. These bacteria are part of the normal flora of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and female genital tract, and they typically require a disruption of mucosal barriers to become pathogenic.[2] The disease often follows abdominal surgery, trauma, or perforation of the intestines, allowing the bacteria to invade deeper tissues.

Epidemiologically, actinomycosis is uncommon, accounting for <1% of all bacterial infections in humans. It affects males more frequently than females and is most common in individuals between 20 and 50 years old. Immunocompromised individuals are at higher risk.

Pathogenesis involves the bacteria spreading contiguously through tissues rather than through the bloodstream, forming characteristic sulfur granules. The infection provokes a chronic inflammatory response, leading to the formation of abscesses, draining sinuses, and fibrosis.[3] The clinical presentation of abdominal wall actinomycosis can mimic other conditions such as tumors or other infections, making diagnosis challenging. Diagnosis often requires microbiological culture or HPE.

Imaging findings in actinomycosis is equivocal and it is a challenge to diagnose this condition radiologically. The findings favorable for actinomycosis includes strong enhancement in the solid component of the mass, tiny rim-enhancing abscesses within the mass, and widespread inflammatory extensions.[4] The aggressive infiltration pattern of abdominopelvic actinomycosis is one of the disease’s key radiologic features which are attributed to the production of proteolytic enzyme by the bacilli. This causes the abdominal wall to become extensively infiltrated with inflammatory fat, leading to the formation of abscesses. In actinomycosis, the organism typically does not spread by hematogenous or lymphatic pathways, and regional lymphadenopathy is uncommon. The presence of extensive and dense fibrosis in actinomycosis is responsible for T1/T2 hypointense signal change on MRI.[5]

Conventional treatment for actinomycosis involves intravenous penicillin for 2–6 weeks followed oral penicillin for 6 months.[6] Nowadays, shorter treatment protocols have evolved but largely depend on the clinical and radiological response to treatment. Surgical debulking may be performed for localized abdominal actinomycosis, followed by short course oral antibiotics. Although actinomycosis is rare in present days, the treatment is not standardized and the clinician should have an individualized protocol and a long-term follow-up keep in mind the recurrence of the condition.

CONCLUSION

Irregular infiltrative enhancing lesions in atypical locations with surrounding inflammation and micro-abscesses without regional lymphadenopathy should raise the suspicion of actinomycosis. Radiologists must be aware of the imaging findings of actinomycosis for prompt diagnosis which will help institute the appropriate treatment earlier.

TEACHING POINTS

Actinomycosis should be a diagnostic consideration in chronic irregular hard masses extending across the tissue plane with surrounding inflammation

Earlier diagnosis of actinomycosis can help the patient get cured by antibiotic therapy alone without the need for surgery. Knowledge about the clinical and radiological findings helps to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions

Infiltrative T2 hypointense masses in atypical locations should raise the possibility of actinomycosis.

MCQs

-

Which Actinomyces species are commonly responsible for human infection?

Actinomyces meyeri

Actinomyces israelii

Actinomyces viscosus

Actinomyces odontolyticus

Answer Key: b

-

T2 hypointense signal change of the actinomycosis lesion is due to?

Amyloid content

Myxoid cellularity

Calcium deposition

Dense fibrosis

Answer Key: d

-

Drug of choice for actinomycosis

Penicillin G

High dose steroids

Third generation cephalosporins

Fluconazole + Erythromycin combination therapy

Answer Key: a

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Actinomycosis In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482151 [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 07]

- [Google Scholar]

- Actinomycosis: Etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-97.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology, clinical presentation and treatment outcomes in CNS actinomycosis: A systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023;18:133.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdominopelvic actinomycosis: Spectrum of imaging findings and common mimickers. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2014;3:2047981614524570.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdominal wall actinomycosis simulating a malignant neoplasm: Case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;2:247-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short-term treatment of actinomycosis: Two cases and a review. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:444-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]